Why Prince Andrew Still Can’t Be Cut from the Throne: The Constitutional Trap Behind a Royal Scandal

Sarah Johnson

December 12, 2025

Brief

Prince Andrew remains in Britain’s line of succession despite being stripped of titles. This analysis explains the constitutional constraints, historical roots, and what his status reveals about the monarchy’s future.

Prince Andrew’s Quiet Constitutional Shield: What His Survival in the Line of Succession Really Reveals About the Modern Monarchy

King Charles III has done almost everything in his personal power to push his disgraced brother to the margins of royal life: titles stripped, military honors removed, residence revoked. Yet Prince Andrew – now Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor – remains eighth in line to the throne. That apparent contradiction isn’t a quirky technicality; it exposes the core tension at the heart of Britain’s constitutional monarchy in the 21st century: can an institution built on bloodline credibly promise accountability in an age obsessed with personal responsibility?

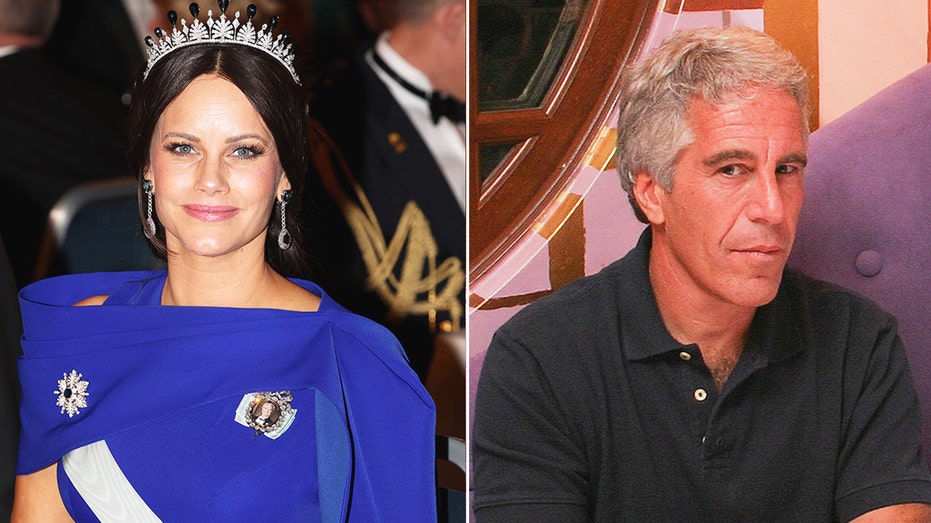

Andrew’s continued place in the line of succession is often dismissed as a symbolic oddity, given how remote his prospects of becoming king now are. But symbols are the monarchy’s currency. The fact that a man forced from public life over his ties to Jeffrey Epstein still occupies a formal place in the chain of sovereignty tells us far more about the limits of royal reform, the fragility of constitutional norms, and Britain’s unresolved reckoning with elite impunity than most mainstream coverage has acknowledged.

The structural problem: a hereditary system in a #MeToo era

To understand why King Charles cannot simply “delete” Andrew from the succession, you have to go back to the architecture of modern monarchy settled after a series of 17th- and 18th‑century crises.

Following the English Civil War, the execution of Charles I (1649), the Glorious Revolution (1688), and the Act of Settlement (1701), Parliament deliberately designed a system where royal bloodline determines the crown, but Parliament sets the rules. The succession is therefore simultaneously automatic and highly constrained:

- Automatic because the next in line is determined by birth, not popularity or merit.

- Constrained because only Parliament (and now, the parliaments of the 15 other Commonwealth realms) can change the rules of who qualifies.

This split was meant as a safeguard against exactly what some are now demanding: a monarch personally pruning the family tree for political or personal reasons. It was a reaction to centuries of royal purges, from Henry VIII’s executions to the deposition of James II. The post‑1688 system tried to make the monarchy predictable, not virtuous.

That design sits uneasily with the expectations of a society shaped by the #MeToo movement, transparency norms and the idea that public roles require moral scrutiny as well as legal compliance. A hereditary system can adjust rules at the margins – as with the 2013 Succession to the Crown Act ending male preference and the ban on heirs marrying Catholics – but it cannot easily accommodate case‑by‑case moral censure without threatening its own logic.

Why Andrew is different from Edward VIII – and why that matters

Commentators often reach for the abdication of Edward VIII in 1936 or earlier exclusions (such as the old Catholic-marriage disqualification) as precedent. But Andrew’s case is fundamentally different in three ways.

- There is no formal abdication mechanism for junior royals. Edward VIII was the reigning king; his abdication required a specific act of Parliament but fitted long-standing ideas about a sovereign’s ability to step down. Andrew is a non-reigning prince. There is no routine legal instrument for him to “abdicate” a place in the line without wholesale statutory change.

- His disgrace is moral and reputational, not constitutional. Earlier exclusions related to religion (seen as a direct constitutional conflict with the monarch’s role as Supreme Governor of the Church of England) or to abdication itself. Andrew’s alleged misconduct – centered on sexual exploitation and abuse of power – is deeply serious but not a direct constitutional violation in the technical sense.

- The international dimension is now far more complex. Any change to the succession rules must be coordinated with all Commonwealth realms. When the 2013 reforms were enacted, each realm passed aligned legislation or gave assent. Re‑opening that process to solve the “Andrew problem” would require careful diplomacy and could reignite republican debates in countries like Australia, Canada, and Caribbean states already rethinking the crown.

So, while there is historical precedent for altering succession rules, the threshold has traditionally been existential or systemic – not reactive to individual scandals. Using that machinery for one disgraced royal sets a precedent future monarchs and politicians may not want to live with.

The real fear in Whitehall: politicising the Crown

Behind the formal legal obstacles lies a more subtle concern: turning the line of succession into an instrument of political pressure.

If Parliament were to legislate Andrew out of the line solely on the basis of his conduct and public unpopularity, three doors open:

- First, succession becomes a tool of political virtue-signalling – MPs rewarding or punishing royals to satisfy public opinion.

- Second, it invites future campaigns to remove other controversial figures: a disgraced heir, a politically outspoken prince, or even a consort seen as divisive.

- Third, it blurs the line between a symbolic constitutional monarchy and a quasi‑elective or “performance‑rated” monarchy, undermining the justification that heredity insulates the crown from partisan battles.

Constitutional scholars quietly point out that the only real protection the monarchy has in a democratic age is its predictability and political neutrality. Once you accept that Parliament can surgically excise a royal from the succession for reputational reasons alone, you effectively invite future parliaments to treat the crown as another political tool. That is precisely what the post‑1688 settlement sought to avoid.

Optics vs. power: why the symbolism still matters

Andrew’s defenders – and some constitutional purists – argue that his position is irrelevant because he is vanishingly unlikely ever to reign. On a purely actuarial basis, that’s true. For Andrew to become king would require a catastrophic and improbable chain of deaths or disqualifications affecting the current king’s children and grandchildren.

But this argument misses the core point: the monarchy trades in symbolism, not executive power. Public perception is not just a side issue; it is the institution’s main currency. Opinion surveys in recent years have shown declining support for the monarchy among younger Britons, and particular disgust over royal association with Epstein and other scandals. Maintaining Andrew in the line – even ineffectually – risks reinforcing a narrative of unaccountable, insulated elites.

At the same time, the palace knows that going to Parliament to “fix” this could backfire. A legislative push to remove Andrew could turn into an open debate on whether Britain needs a monarchy at all. For a government preoccupied with economic challenges and social division, that is a door many would rather keep closed.

Epstein files and the risk of a slow-burn crisis

The looming release of further Epstein-related documents in the US adds another destabilising factor. Even if no new direct legal exposure emerges for Andrew, any fresh detail about his association with Epstein could reignite public outrage and global media scrutiny. The monarchy’s approach so far has been containment: remove Andrew from public duties, minimise his visibility, and hope time dulls public anger.

If new evidence were to seriously challenge Andrew’s denials, the calculus changes. At that point, the argument that the line of succession is purely formal may not suffice. Pressure would grow, not just from campaigners but from within the political class, to demonstrate that even royal blood does not bring automatic constitutional privilege in the face of grave misconduct.

Yet any such move would push Britain into largely uncharted constitutional territory: crafting criteria for when a royal can lose their place in the line based on behavior, without collapsing the principle of hereditary succession altogether.

The unspoken issue: elite impunity and public trust

What often goes unsaid in mainstream royal coverage is how the Andrew saga plugs into broader anxieties about elite impunity. For many observers, the detail that Andrew settled with Virginia Giuffre out of court – with no admission of liability – embodies a familiar pattern: powerful men facing serious allegations using money and influence to avoid full legal scrutiny.

In that context, Andrew’s continued presence – however theoretical – in the line of succession is not just about royal protocol. It becomes a symbol of a system where the most connected are never truly stripped of their status. Even when punished, they remain “in the line” in some way.

Contrast this with the standards applied to many ordinary public servants: police officers, teachers, military personnel or civil servants can lose jobs, pensions and professional standing on much lower thresholds than those applied to a royal prince. The palace and the government are acutely aware of this contrast; it’s one reason why the king pushed so hard to strip Andrew of visible privileges. But without touching the succession, the most potent symbolic connection – the possibility, however remote, of ultimate power – remains.

What a serious reform would actually require

Behind the scenes, constitutional lawyers have sketched possible models for future reform, should the political will ever materialise. They cluster around three concepts:

- Automatic exclusion triggers. Parliament could legislate that any royal within a set number of places in the line is automatically removed if convicted of certain serious offences. This would keep the principle general rather than targeting one individual, but carries the risk of courts being drawn into intensely politicised cases involving royals.

- Independent constitutional commission. A standing body – perhaps akin to a royal-appointments commission – could be empowered to recommend removal from succession in extreme cases, subject to parliamentary approval. That might provide some insulation from partisan politics, but critics would worry about unelected commissioners wielding enormous symbolic power.

- Voluntary renunciation mechanism. A statute could create a formal process by which a royal can permanently renounce their place in the line, with clear legal consequences. That would not solve the Andrew dilemma unless he chose to use it, but it would at least avoid future impasses where a disgraced royal wishes to withdraw but lacks a clean mechanism.

Each approach raises its own knot of questions: what counts as misconduct? Who decides? How do you avoid creating de facto “good behavior” tests for royals that undermine the very point of heredity? The difficulty of answering these questions is one reason there is currently little appetite in Westminster for touching the issue at all.

Why King Charles stopped where he did

Charles’ strategy so far has been to go right up to the constitutional line, then stop. By revoking Andrew’s HRH style, military roles, patronages and key residence, he has sent an unmistakable signal that Andrew has no future in public life. But he has not publicly lobbied to alter the succession – a line he appears unwilling to cross.

There are practical reasons for this restraint: the king knows he must remain politically neutral and avoid lobbying Parliament on core constitutional questions. But there is also a longer view. If Charles normalises the idea that a monarch can invite Parliament to surgically disinherit an unpopular relative, he risks setting a precedent that could one day be turned against his own line, or used in ways he cannot foresee.

In other words, Charles is choosing institutional survival over maximal reputational cleansing. From a purely public-relations perspective, completely cutting Andrew out might be attractive. From a constitutional perspective, it may be dangerously short‑sighted.

Looking ahead: three fault lines to watch

As the Andrew saga enters its next phase, three developments will be particularly important.

- Further Epstein disclosures. Any new material linking Andrew more directly to criminal acts or contradicting his prior denials would intensify demands for formal consequences. Even in the absence of criminal charges, detailed revelations can be politically explosive.

- Commonwealth republican debates. Several Caribbean nations, and to a lesser extent Australia and Canada, are already re‑examining their ties to the crown. Andrew has become a quiet supporting argument for those who claim the monarchy is out of step with modern values.

- Generational attitudes in the UK. Polling consistently shows markedly lower support for the monarchy among under‑35s. For this cohort, Andrew is not a marginal figure from a fading era but a live example of how the institution handles alleged abuses. Their judgments will shape the monarchy’s medium‑term future more than any single scandal.

The bottom line

Andrew’s continued presence in the line of succession is not an oversight; it is a deliberate feature of a system that prioritises stability over moral responsiveness. That design may have made sense in the aftermath of civil war and religious conflict. In an age of #MeToo, transparency demands and rising anger at elite impunity, it looks increasingly out of step.

Stripping Andrew of titles and status without touching the succession represents a compromise between those two worlds. It protects the constitutional logic of hereditary monarchy while acknowledging public outrage. Whether that compromise holds will depend less on lawyers and palace aides than on what emerges from sealed files, how the public reacts – and whether a new generation decides that a system which cannot fully disown its most problematic members is still worth keeping.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s striking in the Andrew debate is how little of it engages with the core question: what is the monarchy actually for in 2025? Supporters often invoke soft power, national identity and constitutional stability, yet the institution continues to behave as if its primary goal is preserving its own internal hierarchy. Andrew’s case exposes that tension brutally. If the monarchy’s legitimacy now rests heavily on projecting moral authority and service, then keeping a figure so decisively removed from public duties still embedded in the line of succession feels like a category error. At the same time, the nervousness in Westminster about opening up succession law suggests ministers recognise how fragile the settlement really is. Once you admit that heredity can be overridden by conduct, you invite the public to ask why heredity should matter at all. The palace may hope that quiet exile and time will dull public anger, but the risk is that Andrew becomes a standing reminder that, when confronted with a choice between principle and survival, the institution chose survival—and people noticed.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.