Inside the Real Start of 2028: How Harris, Newsom, and Pritzker Are Defining the Next Democratic Era

Sarah Johnson

December 12, 2025

Brief

At the DNC’s winter meeting, Harris, Newsom, and Pritzker quietly launch the 2028 battle. This analysis unpacks the calendar fight, coalition strategies, and generational shift shaping Democrats’ next era.

2028 Begins in 2025: What Harris, Newsom, and Pritzker’s DNC Moment Really Signals About the Next Democratic Era

When three likely presidential contenders converge at a party summit years before an election, it’s not just scheduling coincidence — it’s an x-ray of a party trying to decide what it wants to be next. The Democratic National Committee’s winter meeting in Los Angeles is formally about dissecting 2025 results and preparing for the 2026 midterms. In reality, it’s the soft launch of the 2028 Democratic primary, and the presence of Kamala Harris, Gavin Newsom, and J.B. Pritzker on the same stage is a revealing test of power, ideology, and strategy inside the party.

Understanding this moment requires looking past the horse race and into three deeper questions: Who will control the party’s future message? How will Democrats adapt their coalition after a turbulent decade? And what does this early maneuvering tell us about the likely fault lines of 2028 — not just among candidates, but among competing theories of how to beat the post-Trump Republican Party?

The quiet start of a post-Biden, post-Trump Democratic Party

The last decade of Democratic politics has been dominated by three forces: the Obama coalition, the Trump backlash, and the Biden-era push for stability and institutional repair. The 2028 cycle will be the first truly post-Trump-era race where both parties are, in theory, looking beyond Trump himself and Joe Biden’s generation.

Harris, Newsom, and Pritzker each represent a different answer to a question Democrats have been struggling with since 2016: Is the party’s future built on identity and representation, on blue-state progressive governance, or on pragmatic economic populism aimed at the Midwest and Sun Belt?

- Kamala Harris offers continuity with the national ticket and symbolic representation: the first woman, Black, and South Asian vice president who remains a powerful figure for the party’s base and donor class.

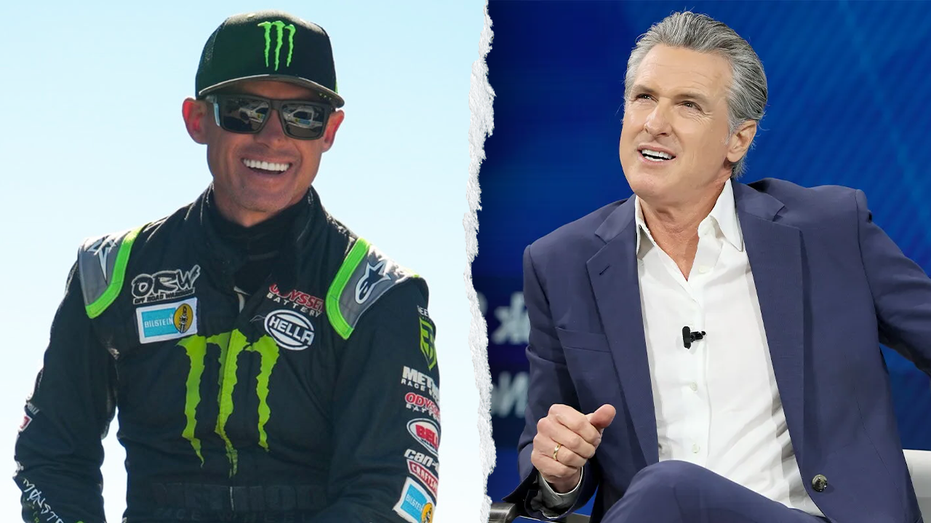

- Gavin Newsom is the embodiment — and lightning rod — of West Coast progressivism, packaging social liberalism with aggressive climate and cultural messaging.

- J.B. Pritzker brings the Midwestern executive model: big spending, labor-friendly economic populism, and a strategic focus on swing-region viability.

Their convergence at the DNC is less about 2026 logistics than about something more fundamental: which of these models can unify an increasingly fragmented Democratic coalition that now includes suburban moderates, younger leftists, voters of color whose partisan loyalty is slowly softening, and disaffected anti-Trump Republicans.

Why an internal calendar fight may define the 2028 field

The article briefly mentions what sounds like an obscure procedural battle: the looming fight over the 2028 presidential nominating calendar. This is actually one of the most consequential subplots for 2028, and it explains why these potential contenders are already logging trips to South Carolina, New Hampshire, Nevada, and other early states.

In 2024, Democrats took the historic step of elevating South Carolina — a state with a large Black Democratic electorate — to the first spot on the official primary calendar, displacing New Hampshire’s century-old hold on the “first-in-the-nation” status. That fight left scars inside the party. New Hampshire still held an unsanctioned primary and significant figures in the party quietly opposed the reordering.

Now, as the DNC’s Rules and Bylaws Committee gears up to revisit the calendar for 2028, the stakes are clear:

- If South Carolina stays first, that structurally advantages candidates with deep ties to Black voters and party regulars – a potential boost for Harris, who benefited from South Carolina powerbrokers in 2020–24, and for any candidate closely aligned with the current DNC leadership.

- If New Hampshire and Nevada regain leverage, that potentially favors candidates who can appeal to more independent-minded and working-class white voters, as well as union-heavy Western states – a space where Pritzker or Midwestern governors like Gretchen Whitmer or Josh Shapiro might thrive.

- Newsom’s trip to South Carolina and Pritzker’s visits to New Hampshire and Nevada are less about ‘introducing themselves’ and more about staking a claim in the calendar fight itself. Early state alliances often shape not just momentum but media narratives and donor flows.

The public will experience this as a 2028 “momentum” story. Insiders understand it as a structural design choice that could tilt the entire field toward one kind of candidate or another. That’s why this DNC summit — where Rules Committee leaders, state chairs, and rising stars mingle in private — matters far more than the bland agenda suggests.

Three candidates, three theories of how Democrats win

What’s really being tested in Los Angeles is not just personal ambition but competing theories of how to win a general election in a rapidly shifting electorate.

1. Harris: The continuity and coalition theory

Harris’s message — “I am not done… it’s in my bones” — positions her as a lifelong public servant whose story is intertwined with the party’s recent history. Her implicit pitch is that the coalition that elected Biden-Harris can be modernized and led by someone who looks more like the party’s base.

The advantages of this approach:

- Base familiarity: She is already a national figure, reducing the “introduction” costs other candidates will face.

- Symbolic power: Her identity continues to resonate with key segments of the Democratic coalition, particularly Black women, who remain among the most loyal Democratic voters.

- Institutional ties: Deep relationships with DNC leaders, donors, and activists built during the Biden-Harris cycles.

The challenges are equally real: her underwater favorability ratings during her vice presidency, persistent questions about her retail political skills, and the risk that voters looking for generational or stylistic change may see her as part of a political era they want to move past rather than forward.

2. Newsom: The “California as counter-Trump” theory

Newsom has spent years positioning California as a kind of ideological anti-red-state, especially on issues like abortion, gun safety, climate, and immigration. His strategy is to present progressive governance not as coastal excess, but as a model for national resilience and rights protection in a post-Roe, post-Trump era.

This theory of victory assumes:

- Culture wars help Democrats when framed around freedoms — reproductive rights, speech, and democracy — rather than abstract ideology.

- Blue-state experimentation can be turned into national policy vision rather than used as a GOP attack line on taxes, crime, or homelessness.

- Media combativeness (his willingness to publicly spar with conservative governors and pundits) energizes the base and breaks through an oversaturated media environment.

But California’s brand cuts both ways. In national polling over the last decade, California is often cited by swing voters as shorthand for high costs, perceived disorder, and elite liberalism. A Newsom candidacy would test whether Democrats can run not away from progressive governance, but directly on it — and whether persuadable Midwestern and Sun Belt voters are open to that argument.

3. Pritzker: The Midwestern economic populism theory

Pritzker’s approach is more technocratic but no less ambitious: show that big-government liberalism can produce tangible results for working- and middle-class voters in a purple-leaning region. Illinois under Pritzker has raised the minimum wage, expanded reproductive and LGBTQ rights protections, and invested heavily in infrastructure and social services.

The theory here is that Democrats can rebuild their “blue wall” and make gains in states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin by leaning hard into economic populism while keeping social issues firmly liberal but less theatrically so than on the coasts.

This approach bets that:

- Kitchen-table economics remain the central battleground after years of democracy and identity-focused messaging.

- Blue-collar and suburban voters can be held together with a mix of economic security policies and competence-focused governance.

- Donor-class wealth (Pritzker is a billionaire) can be politically reframed as a tool for progressive causes rather than a liability.

The open question: Does a billionaire Midwestern governor become an ideal foil for Republicans — or a Democratic version of their own “successful businessman” narrative, but tied to union-backed, pro-safety-net policies?

The overlooked story: 2028 as a generational transition, not just a personality contest

Most coverage will frame 2028 as Harris vs. Newsom vs. Pritzker vs. everyone else. What’s more important is that 2028 is likely to be a profound generational transition — not just in age, but in political experience.

For the first time since 2008, the likely Democratic nominee will be someone whose political identity was shaped by the Trump era as much as by the Cold War or civil rights movements. Many of the other potential contenders mentioned — Gretchen Whitmer, Josh Shapiro, Wes Moore, Andy Beshear, Cory Booker, Pete Buttigieg, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez — came of age politically in a world defined by polarization, social media, and mass disinformation.

That generational shift matters because it may produce candidates who:

- View disinformation and platform regulation as core governing issues, not side debates.

- Are more comfortable with multi-racial, multi-class coalitions that include both anti-MAGA Republicans and disillusioned young progressives.

- Frame climate, technology, and inequality as intertwined, not separate issue silos.

The DNC winter meeting is where these leaders quietly test how far they can push that generational and thematic reset without alienating the party’s older institutional backbone.

Data points: Why the 2026 midterms are the proving ground

The DNC member quoted in the piece is blunt: 2026 is the immediate focus, but it’s also the proving ground for 2028 narratives. Historically, midterm performance has shaped presidential viability:

- After Democrats’ strong performance in the 2006 midterms, Nancy Pelosi and a new generation of leaders gained power, strengthening Barack Obama’s argument that he represented a movement, not just a candidacy.

- The party’s 2010 midterm losses constrained Obama’s legislative agenda and fueled intra-party debates that resurfaced in the 2016 primary between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

- Democrats’ 2018 blue wave against Trump helped normalize more aggressive progressive messaging and lifted figures like Ocasio-Cortez into national prominence.

If Democrats deliver another strong midterm performance in 2026 — flipping or expanding control of the House, and potentially the Senate — the 2028 contest will likely center on which candidate can scale that strategy nationally. If they stumble, the party may look toward more disruptive or outsider candidacies promising to rethink strategy from the ground up.

Potential contenders know this. That’s why the article notes they’ll be “very engaged” in House and Senate races: they aren’t just building goodwill; they’re test-running messages, consultants, digital strategies, and local alliances that can become the skeleton of a presidential campaign.

What to watch next: Signals that will matter more than the speeches

The speeches at the DNC winter meeting are largely theater. The real signals to watch in the coming 12–18 months include:

- Who builds early-state infrastructure first. Hiring experienced operatives in South Carolina, New Hampshire, Nevada, and emerging battlegrounds like Georgia and Arizona is often a more telling sign than public denials about 2028 ambitions.

- Who becomes the face of the 2026 midterm message. The DNC and congressional leaders will inevitably promote a handful of figures as key surrogates. Watch which potential 2028 contenders get slotted into high-visibility roles on abortion, democracy, inflation, and immigration.

- How the nominating calendar fight resolves. Any compromise that preserves South Carolina’s early role while mollifying New Hampshire and Nevada will tell you which faction of the party is currently winning the internal argument about its base.

- Donor consolidation. Silicon Valley, Wall Street, Hollywood, and union donors will start informally picking favorites. Even without max-out contributions, the density of joint appearances and fundraising events is a key signal.

The bottom line

On paper, the DNC winter meeting is just another party summit. In practice, it’s the soft opening of the 2028 Democratic primary and the beginning of a deeper argument about what kind of party Democrats want to be in the post-Biden, post-Trump era.

Harris, Newsom, and Pritzker are not simply jockeying for position; they are field-testing three different theories of how Democrats can knit together an uneasy coalition, win back or solidify key states, and respond to a Republican Party that may or may not still be defined by Trump in 2028.

What happens in these rooms — the private conversations, promises, and alignments around the nominating calendar and midterm strategy — may ultimately matter more than any future debate stage. By the time voters are paying attention to 2028, much of the structure of that race will already have been quietly built at meetings like this one.

Topics

Editor's Comments

What’s striking about this moment is how much of the 2028 story is being written by people who will never appear on a ballot. State party chairs, Rules Committee members, and major donors are using meetings like this to negotiate the shape of the playing field: which states vote first, how much emphasis falls on base versus swing voters, and which kinds of candidates are encouraged to step forward. The public tends to see presidential primaries as organic contests of charisma and ideas. In reality, they are heavily structured competitions, and the “invisible” decisions made in 2025 and 2026 will either widen or narrow the lane for figures like Harris, Newsom, Pritzker, and their rivals. One under-covered risk is that a calendar designed to reward certain factions — say, heavily institutional or heavily progressive candidates — could unintentionally sideline contenders who might be stronger in a general election. That tension between primary incentives and general-election needs is where the party’s internal debates could turn most consequential, and most contentious, over the next two years.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.