Europe’s Cocaine Flood: How Narco-Subs Expose a Dangerous New Drug Order

Sarah Johnson

December 12, 2025

Brief

Narco-subs ferrying cocaine across the Atlantic are a symptom of a deeper shift: Europe has become a primary cocaine market. This analysis explains the structural drivers, risks, and geopolitical stakes.

Europe’s Cocaine Flood: Why Narco-Subs Are a Symptom of a Much Deeper Crisis

Europe’s warning that it is “literally being flooded with cocaine” is not hyperbole. It is a signal that the global drug economy has decisively pivoted toward Europe, and that law enforcement is once again playing catch-up with a hyper-adaptive criminal market. The rise of transatlantic narco-subs is dramatic, but the real story is how these vessels reveal deeper structural shifts: in global trade routes, in European demand, and in the geopolitics of drug enforcement.

The Bigger Picture: How Europe Became the New Growth Market for Cocaine

For decades, the United States was the primary destination for Latin American cocaine. That balance has changed. Over roughly the last 15–20 years, Europe has emerged as a booming parallel market. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has documented a steady rise: cocaine seizures in the EU more than quadrupled between 2010 and 2022, and purity levels on the street have increased rather than fallen—classic signs of a saturated but still expanding supply.

Three structural trends drove this pivot:

- Profit differentials: Wholesale prices for cocaine in Europe remain significantly higher than in the U.S., with some estimates placing them 50–100% above U.S. levels. For traffickers, crossing the Atlantic is high risk but even higher reward.

- Shifts in U.S. enforcement and consumption: As U.S. law enforcement intensified interdiction and domestic demand shifted toward synthetic opioids like fentanyl, Latin American cartels diversified markets. Europe, with its relatively affluent consumer base, became strategic.

- Global trade integration: Europe’s vast, high-volume port system—Rotterdam, Antwerp, Hamburg, Algeciras, and others—offers traffickers both opportunity and cover. Container shipping and complex supply chains provide the perfect camouflage for drug loads.

Historically, Europe saw cocaine trafficking largely as an issue of organized crime and public health, not national security. That framing is now colliding with reality as cartels leverage quasi-military tactics and technology, including semi-submersible vessels designed to defeat modern surveillance.

Why Narco-Subs, and Why Now?

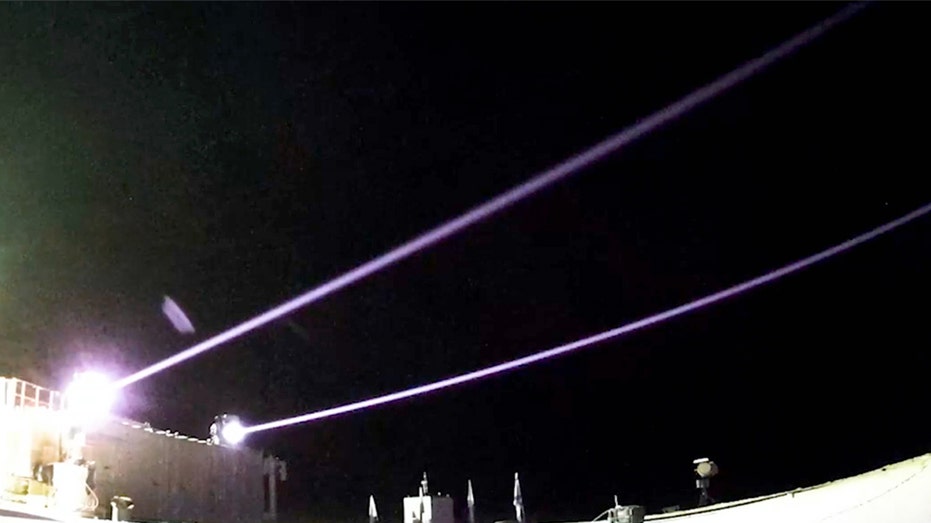

Narco-subs—low-profile vessels or semi-submersibles that skim just below the surface—first appeared in the Eastern Pacific in the late 1990s. Initially, they were primarily aimed at the U.S. market via Central America and Mexico. What’s new is their ability and willingness to cross the Atlantic to reach Europe directly.

This evolution reflects two key dynamics:

- Adaptation to enforcement pressure: As surface interdiction of go-fast boats and commercial cargo intensified, traffickers invested in vessels that dramatically reduce radar visibility and visual detection. Painting hulls in blues and grays, hugging sea states, and keeping profiles just above the waterline are all deliberate countermeasures.

- Decentralized innovation: Cartel engineering is no longer a crude, improvised affair. It now resembles a distributed R&D system. Workshops in Colombia, Ecuador, and Brazil iterate on designs, with each interception feeding back into improvements. The shift from coastal routes to transoceanic voyages shows how quickly tactics can evolve when profits justify experimentation.

The estimated interdiction rate of just 5–10% for these vessels is telling. It suggests that what authorities see is a small fraction of what’s actually moving—a typical pattern in drug markets, where seizure data usually represent the tip of the iceberg.

What This Really Means: Security, Governance, and the Human Cost

Focusing solely on the technology of narco-subs obscures deeper implications.

1. A Strategic Shift in Criminal Power

Direct transatlantic narco-sub routes indicate that Latin American cartels and allied networks are confident Europe is a low-risk, high-yield environment. As former DEA official Derek Maltz notes, these groups do not yet perceive Europe as a serious threat to their business model. That perception gap has consequences:

- Criminal ecosystem building: Large, steady flows of cocaine create incentives for European and West African organized crime groups to integrate more deeply with Latin American suppliers. We are seeing the emergence of integrated transnational networks rather than isolated cartels.

- Port capture and corruption: Reports in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Spain already document worrying levels of port-worker intimidation and corruption. As profits grow, so does the incentive to infiltrate customs, shipping, and logistics.

2. Europe’s Legal and Ethical Dilemma

The contrast between U.S. operations, which reportedly involve destroying vessels and killing crews at sea, and Europe’s approach—intercept, arrest, interrogate—reflects deeper legal and political choices.

- Rule-of-law constraints: European states are constrained by the European Convention on Human Rights and their own constitutional frameworks. Summary destruction of vessels and lethal force without clear imminent threat would spark legal challenges and public backlash.

- Intelligence over spectacle: By arresting crews rather than sinking boats, European agencies aim to map networks—routes, financiers, logisticians. This is slower and less visually dramatic but potentially more effective for long-term dismantling of organizations.

Yet this approach has limits. As one Portuguese official acknowledges, crews are typically “desperate people” at the lowest rung of the chain—often easily replaceable and holding limited strategic information. The strategic brains and financial architects rarely touch the water.

3. The Human Disposability at the Heart of the Trade

The description of crews locked in tiny, fume-filled compartments for days, sometimes found dead on arrival, highlights a brutal truth: in this business model, human beings are expendable logistics assets. For kingpins, a lost crew is a write-off; the true loss is only the cargo.

This mirrors a wider pattern in illicit economies: the poorest take the highest physical risks for the smallest share of revenue. From coca farmers in Colombia to dock workers in Antwerp to sub crews in the Atlantic, the drug economy reproduces and exploits existing inequalities.

Expert Perspectives and Overlooked Dimensions

Experts in organized crime and security see several under-discussed aspects of this shift.

Ports, Not Just Seas, Are the Real Battleground

Dr. Felia Allum, a scholar of organized crime, has argued that focusing on high-seas interdictions can be misleading: the real leverage point is at the interface of legitimate and illegitimate trade—ports, logistics companies, and financial systems. Narco-subs are spectacular, but most cocaine still arrives via containers on commercial vessels.

In that sense, narco-subs may serve an auxiliary function: probing enforcement coverage, testing routes, and supplementing larger flows rather than replacing them.

The West African and North African Connection

While the article highlights mid-Atlantic interceptions, many transatlantic routes intersect with West Africa and the Sahel. For over a decade, UN and EU reports have documented cocaine moving from Latin America to coastal states like Guinea-Bissau, then onward through the Sahara toward North Africa and into Europe.

This creates a dangerous fusion of drug trafficking with other security threats, from jihadist insurgencies in the Sahel to human smuggling across the Mediterranean. Cocaine money can lubricate arms purchases, corruption, and insurgent financing.

Digital Logistics and Invisible Kingpins

Modern cocaine networks are increasingly platform-like, using encrypted communications, compartmentalized logistics, and freelance crews. The image of a single omnipotent cartel boss is outdated. Instead, we see loosely coupled networks linking producers, transporters, corrupt officials, and European distributors who often operate semi-independently.

This makes the “decapitation” strategy—arresting top leaders—less effective. The system is designed to survive leadership losses, with logistics and financial channels persisting.

Data & Evidence: What the Numbers Signal

Several quantitative indicators support the narrative of a European cocaine surge:

- Record seizures: EU-wide seizures surpassed 300 metric tons annually in recent years, with individual hauls of several tons increasingly common—suggesting that traffickers are moving larger consignments to optimize risk.

- Rising purity and stable prices: Street-level purity in many European cities has climbed, while prices remain relatively stable. In basic economic terms, this typically signals a robust and resilient supply chain.

- Geographic spread: Cocaine is no longer confined to traditional Western European markets; Eastern and Northern Europe are seeing sharper growth in consumption, expanding the customer base.

Against this backdrop, a single intercepted narco-sub carrying 1.7 metric tons is both a success and a warning: if interdiction rates are indeed around 5–10%, the total volume moving by these routes is likely far higher.

Looking Ahead: What to Watch Beyond the Headlines

Several emerging dynamics will shape how this story evolves.

1. Militarization vs. Law Enforcement

There is growing tension between calls for a more “muscular” response and Europe’s legal commitments. If the U.S. continues to favor kinetic operations—blowing up boats, lethal engagements—pressure may build on European governments to harden their stance.

The risk: a slide toward a more militarized, extraterritorial drug war model without clear evidence that such tactics reduce supply in the long term. Past experience in Latin America suggests that heavy militarization often displaces routes and amplifies violence without collapsing markets.

2. Policy Focus: Demand, Treatment, and Regulation

European drug policy has traditionally leaned more toward public health approaches than the U.S., with a stronger emphasis on harm reduction and treatment. Yet cocaine has often been treated as a “party drug” of the middle and upper classes, with less political urgency than opioids.

If Europe is truly being “flooded,” there will be growing pressure to confront domestic demand more seriously: better treatment access, early intervention for problematic use, and confronting the social normalization of cocaine in certain professional and nightlife cultures.

3. The Next Technological Leap

Narco-subs are likely not the endpoint of innovation. Already, analysts are watching for:

- Fully autonomous unmanned narco-vessels guided by GPS and pre-programmed routes, reducing human risk and complicating legal attribution.

- Greater use of drones and hybrid air–sea methods, particularly for shorter hops between coastal departure points and motherships.

As long as the profit margins remain enormous and demand strong, traffickers will continue to invest in technologies that erode the effectiveness of traditional surveillance.

The Bottom Line

Europe’s narco-sub problem is not just a dramatic maritime cat-and-mouse game. It is a symptom of a reconfigured global cocaine economy in which Europe is now a central pillar, not a side market. The vessels skimming beneath the Atlantic waves tell a story about more than smuggling tactics: they reveal gaps in European enforcement, the disposability of the poorest participants, and the growing convergence of global criminal networks.

Unless European states confront both supply and demand—strengthening port governance, addressing corruption, investing in intelligence, and tackling domestic consumption—the Atlantic will remain a busy highway for those willing to risk everything in the dark, cramped hull of a narco-sub.

Topics

Editor's Comments

One dimension that deserves more public debate is the quiet normalization of cocaine consumption within Europe’s professional and political classes. Policy discourse often treats cocaine as a problem of marginalized users or street-level dealing, yet a significant share of demand comes from relatively affluent users whose lives are far removed from the violence and exploitation underpinning the supply chain. This discrepancy shapes political will: it is easier to invest in maritime interdiction and high-tech surveillance than to confront uncomfortable questions about domestic consumption among elites, corporate cultures that tacitly tolerate drug use, or nightlife economies dependent on stimulant-driven spending. Another overlooked issue is the environmental footprint of this trade. From clandestine jungle labs to ocean-going narco-subs abandoned or sunk at sea, the ecological damage is considerable but largely invisible in policy discussions. If Europe is serious about tackling the cocaine flood, it must move beyond spectacular seizures and address the complicity embedded in its own social and economic structures, including who benefits from the current status quo and who pays the price.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.