Jerusalem’s Fallen Hasmonean Wall: How Ancient Rulers Weaponized Demolition and Memory

Sarah Johnson

December 12, 2025

Brief

A newly uncovered Hasmonean wall in Jerusalem is more than a Hanukkah-era relic. It exposes how ancient rulers wielded demolition, diplomacy and urban design to rewrite power and memory.

Unearthing a Fallen Wall in Jerusalem — And a Battle Over Who Gets to Own Its Past

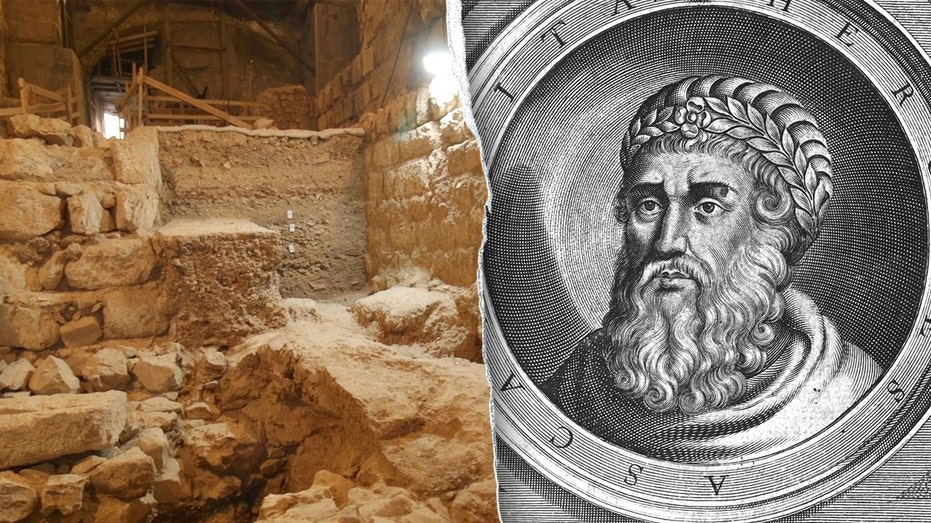

Archaeologists in Jerusalem have uncovered a remarkably preserved stretch of the Hasmonean city wall — more than 130 feet of fortifications from the Maccabean era, later systematically demolished in an ancient political power struggle. On its face, this is a story about stones and ruins. In reality, it’s about the way rulers, ancient and modern, fight not only over territory but over historical narrative itself.

The wall, likely completed in the late second century B.C., sat at the intersection of three overlapping worlds: the fading Seleucid Empire, the rising Hasmonean Jewish state born from the Maccabean revolt, and the looming Roman order that would reshape the region. The fact that this wall was not simply eroded by time but deliberately razed turns it into a political document in stone — one that still has implications for how Jerusalem’s past is contested today.

Why this discovery matters now

Most headlines will frame this as a Hanukkah-era archaeological find. But the deeper significance lies elsewhere:

- It provides the best physical evidence yet for a key phase in Jerusalem’s urban and military development under the Hasmoneans.

- It offers a rare, material window into an ancient political transition: from Hasmonean independence to Herodian-Roman dominance.

- It shows how rulers literally dismantle their predecessors’ defenses and monuments to enforce new political realities and rewrite collective memory.

- It feeds into the modern struggle over archaeological storytelling in Jerusalem — whose history is told, and to what end.

From Maccabees to Herod: the long shadow of a short-lived kingdom

The wall dates to the Hasmonean dynasty, the ruling family that arose from the Maccabean revolt against Seleucid rule in the second century B.C. For many Jews, that revolt — commemorated by Hanukkah — symbolizes resistance to foreign oppression and defense of religious freedom. But the dynasty it produced rapidly became entangled in power politics, internal factionalism and foreign alliances.

After Judas Maccabeus and his brothers secured religious and partial political autonomy, their successors expanded into a more conventional kingdom. By the late second century B.C., rulers like John Hyrcanus and Alexander Jannaeus were waging campaigns, minting coins and reshaping Jerusalem’s topography. Building and upgrading city walls was central to that project: they broadcast sovereignty, protected key religious and administrative sites and asserted control over trade routes.

Ancient historian Flavius Josephus, writing in the first century A.D., described Jerusalem’s Hasmonean fortifications as formidable and strategically layered. The newly uncovered segment — thick, meticulously built and once over 10 meters high with towers — aligns closely with these accounts, lending concrete support to texts that have long been debated by scholars.

The wall sits in an area that later became part of Herod’s monumental citadel complex, near today’s Tower of David Museum. Herod, a Roman-backed king who ruled from 37–4 B.C., was obsessed with building and rebuilding — palaces, fortresses, and most famously the massive expansion of the Second Temple platform. But he was equally concerned with erasing traces of rival dynasties, including the Hasmoneans, whose legitimacy he both inherited and undermined.

Destruction as a political tool

Excavators Amit Re’em and Marion Zindel emphasize that the wall’s demolition was systematic and intentional, not the product of slow decay or a chaotic siege. That matters because deliberate dismantling of fortifications is typically the result of high-level policy decisions: peace terms, regime change, or a conqueror’s strategy to prevent future rebellion.

Researchers currently focus on two main scenarios, both rooted in military and political calculation:

- A forced bargain with a foreign power: The Seleucid king Antiochus VII Sidetes besieged Jerusalem around 134–132 B.C. Ancient sources suggest that as part of a negotiated settlement, he required the city’s fortifications to be dismantled. The newly discovered destruction could be the physical evidence of that compromise — a moment when the Hasmoneans traded stone defenses for political survival.

- Herod’s rewriting of the city: Several decades later, Herod may have ordered the wall’s dismantling as part of a broader campaign to reshape Jerusalem in his own image and weaken any lingering Hasmonean power base. The message would be clear: the Hasmonean era is over; Herod rules now, with Rome behind him.

Both theories point to a central theme: walls are not just military structures. They are symbols of sovereignty. To destroy them is to declare a regime’s end — and to broadcast who now controls the city’s story.

What this reveals about ancient Jerusalem’s internal conflicts

Modern audiences tend to imagine ancient Judea mainly in terms of external empires: Seleucid, Hasmonean, Roman. The wall’s destruction highlights something often underplayed in popular narratives: the degree to which Jerusalem’s fate was shaped by internal Jewish politics and rival elites.

The Hasmonean period, for instance, saw intense conflict between:

- Religious factions (Pharisees, Sadducees, later Essenes), each with different visions of law, temple authority and relations with foreign powers.

- Royal claimants, including different branches of the Hasmonean family and, later, Herod with his Idumean background and Roman patronage.

- Urban and rural interests, as Jerusalem grew in political and economic importance.

In such a context, dismantling a wall was not just about appeasing a foreign king or upgrading the city’s defenses. It was about weakening rival factions inside the city, changing how pilgrims and soldiers accessed key areas and physically breaking the continuity between one regime’s capital and the next.

Archaeology as a battlefield of memory

The location of the find — within the Tower of David Jerusalem Museum, soon to house a new Schulich Wing of Archaeology, Art and Innovation — underscores another layer: the politics of how Jerusalem’s past is curated for the public.

Visitors will eventually stand on a transparent floor above these Hasmonean stones, accompanied by contemporary artistic interpretations. That framing is not neutral. It reflects choices about:

- Which periods to highlight (Hasmonean, Herodian, Roman, Islamic, Crusader, Ottoman, modern).

- How to connect a Jewish independence era (the Maccabees) with later rulers like Herod and, implicitly, with present-day narratives about sovereignty and indigeneity.

- Whether to emphasize continuity (“Jerusalem’s heritage across 3,000 years”) or rupture (“this dynasty fell; another seized control; outside empires intervened”).

Archaeological discoveries in Jerusalem often become instruments in contemporary debates about ownership, rights to the city and national identity. The story of a wall built by the Maccabees and possibly destroyed under conditions imposed by a foreign king or a Roman vassal will inevitably be read through modern lenses — as a cautionary tale about the fragility of independence, or as a celebration of Jerusalem’s capacity to endure successive empires.

Expert perspectives: stones that speak politics

Several strands of scholarly work help frame this find:

- Urban archaeology has shown that Jerusalem’s defensive lines shifted repeatedly. Scholars like Hillel Geva and Katharina Galor have mapped successive walls from the Iron Age through the Ottoman period, revealing how each regime reoriented the city’s boundaries and priorities.

- Hasmonean studies by historians such as Martin Goodman and Tessa Rajak emphasize how quickly the revolutionary Maccabean movement evolved into a conventional regional power, complete with realpolitik compromises and internal repression. A wall built in their name but later destroyed under pressure encapsulates that arc.

- Herodian architecture, studied extensively by Ehud Netzer and others, demonstrates Herod’s tendency to reuse, overwrite and monumentalize earlier structures — a pattern that supports the idea he might dismantle older fortifications to impose a new urban logic and narrative.

The presence of ancient arrowheads at the site adds a tactical dimension: the wall was not merely ceremonial. It had seen or prepared for combat. Whether those projectiles are linked to Sidetes’ siege, to a later conflict or to training and skirmishes remains an open technical question, but they underscore the sense that this was a lived, contested military frontier within the city itself.

Data points and what they tell us

Some key details help situate the discovery:

- Dimensions: Over 130 feet (c. 40 meters) long and 16 feet (c. 5 meters) wide, with an original height exceeding 10 meters. These are not modest community walls; they represent a substantial state investment in labor and quarrying.

- Construction style: Large stones with a chiseled boss — a projecting central face — typical of the late Hellenistic period in Judea and of elite construction. This confirms it was part of major civic-military infrastructure, not an ad hoc barrier.

- Historical reference: Josephus’s description of an “impregnable” wall with 60 towers gives a textual counterpart. Matching archaeology to such literary descriptions can refine debates about where exactly Josephus’s lines ran and how reliable his urban topographies are.

Together, these data points transform the wall from an isolated ruin into a test case for reconstructing Jerusalem’s layout in the late Second Temple period — a contentious and heavily studied question with implications for everything from biblical interpretation to heritage tourism.

Looking ahead: what to watch for

Several unresolved issues will shape how this discovery is interpreted over time:

- More precise dating of the destruction layer: Radiocarbon dating of organic material, pottery typology and numismatic evidence (coins) could tip the balance between the Sidetes versus Herod hypotheses — or reveal a more complex sequence of damage and rebuilding.

- Integration with other Hasmonean fortification finds: As additional segments and associated structures are uncovered, archaeologists may be able to reconstruct a more continuous line of defense and understand how it interacted with gates, roads and religious precincts.

- Public presentation and narrative framing: How the Tower of David Museum chooses to tell this story — as an emblem of Jewish resilience, as part of a broader imperial chessboard, or as a case study in the politics of memory — will influence public understanding for years.

- Use in contemporary discourse: In a city where history is frequently mobilized in legal, diplomatic and ideological arguments, expect different actors to selectively highlight aspects of this find: independence, foreign pressure, internal division, or continuity of presence.

The bottom line

This Hasmonean wall and its deliberate destruction remind us that Jerusalem’s history is not a simple tale of invasion from outside. It is a layered story of local rulers negotiating, resisting and sometimes capitulating to larger powers — and of each regime reshaping the city’s stone skeleton to assert its own legitimacy.

In that sense, the newly exposed wall is less a relic of the past than a mirror of the present. The same questions run through both eras: Who gets to fortify the city? Who can demand those walls be torn down? And who will decide, centuries later, how that story is told?

Topics

Editor's Comments

What makes this discovery particularly telling is not the wall’s existence but its intentional destruction. We tend to read ancient Jerusalem through the lens of external domination — Hellenistic kings, Rome, later Islamic and Crusader powers — and miss how much agency local actors exercised, even under constraint. The two leading explanations for the wall’s demolition both involve decision-making by Judean elites under pressure: bargaining away fortifications to end a siege, or recalibrating the city’s layout to consolidate a new regime. That nuance matters for modern debates. Narratives that portray Jerusalem solely as a victimized city can obscure moments when its leaders actively reshaped their own defenses, institutions and alliances, sometimes for short-term gain at long-term cost. This wall is a reminder that sovereignty is rarely absolute; it is negotiated, often in stone. As further data emerge, journalists and historians should resist the temptation to cast the find as a simple morality tale of resistance or betrayal. The truth is messier — and more instructive for today’s power struggles, where cities again become bargaining chips and symbols in larger geopolitical games.

Like this article? Share it with your friends!

If you find this article interesting, feel free to share it with your friends!

Thank you for your support! Sharing is the greatest encouragement for us.